Thoughts on entertainment KabukiNo.2

The dynamism of the hanamichi

What point of a Kabuki performance is the most exciting?

I’m sure everyone has their own answers.

But I’m sure many will agree that the moment the small agemaku curtain rises, accompanied by jingling, and lets a popular actor onto the hanamichi runway has a heart-throbbing effect not comparable to anything else.

The actor then proceeds to walk the hanamichi cutting between the seats to the stage. At times, briskly, at times, gloomily. At other times, taking plenty of time to introduce himself.

This moment called de further serves to build up our excitement.

I honestly think this hanamichi is a magical stage structure that makes Kabuki what it is.

When I had just started to watch Kabuki, the hanamichi would remind me of professional wrestling venues.

In large venues like the Tokyo Dome, hanamichi are often built from the wrestlers’ entrances to the ring.

It was when I watched the program Kotobuki Soga no Taimen (The Felicitous Soga Encounter) at the Kabukiza Theatre.

Kudo Suketsune is an important statesman under Minamoto no Yoritomo and has been appointed to head a hunt that is to take place at the foot of Mt. Fuji. Many feudal lords and courtesans (Oiso no Tora and Kewaizaka no Shosho) have come to Kudo’s residence to celebrate.

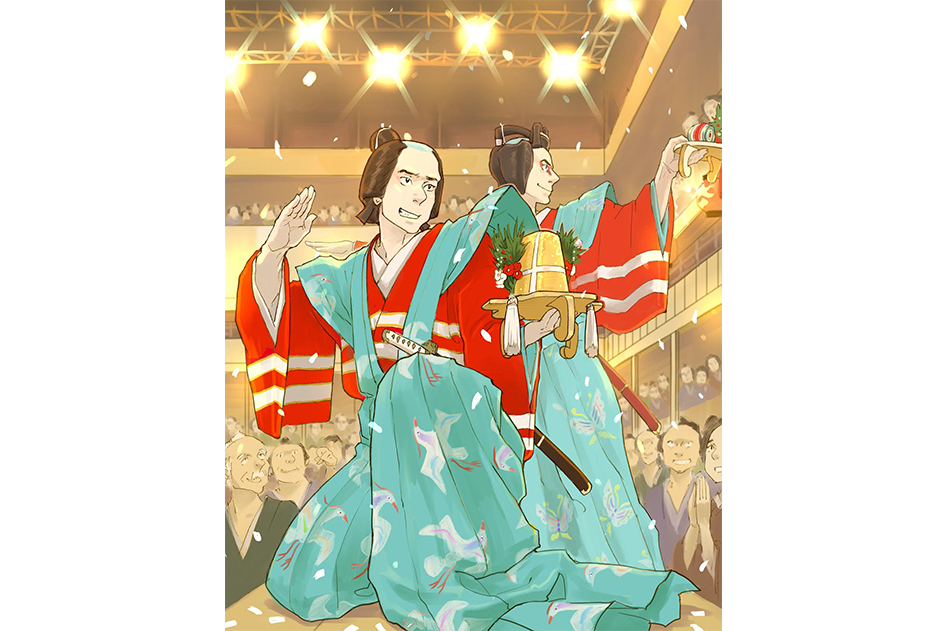

Then, with a jingle, the agemaku rises, and two young men enter the hanamichi. They are the Soga brothers Juro and Goro, sons of Kawazu Saburo, a man who had been assassinated by Kudo.

Time for vengeance.

The Soga brothers march down the hanamichi to crash the banquet, both wearing kimonos colored asagi-iro, light indigo. This costuming makes it feel even more like a pro-wrestling tag team (though the coloring actually indicates their young shabbiness).

The brawling little brother (Goro) and the older brother who calmly handles him (Juro) definitely call to mind Terry Funk and Dory Funk Jr., of the sibling tag team The Funks.

Goro’s striking mie pose with one leg forcefully out certainly has the air of entering the ring.

With ōmukō calls from the audience like a ring announcer . . .

“Hey! Hey! Hey! Kudo!!”

. . . Goro doesn’t quite shout that, of course, but the kind of dynamism making me imagine such a mic performance had been distilled into Goro and Juro’s de on the hanamichi.

The audience is excited, like at pro wrestling at a dome venue.

Actually, though, it’s the opposite.

It’s the pro wrestling hanamichi that has been influenced by Kabuki.

On the Kabuki hanamichi, the spot that is 70% of the way from the agemaku to the stage (with 30% of the way remaining) is called shichi–san “seven–three,” and an actor usually makes some sort of movement or strikes a mie there in most programs.

Some say that, previously, shichi–san referred to the opposite: 30% of the way from the agemaku, closer to it than is now the case. I suppose we could call it “san–shichi.”

Either way, the actor stops partway on the hanamichi once to draw all audience eyes to him to create spatial tension, literally increasing intensity.

Come to think of it, the popular ‘pro wrestling ringmaster’ Keiji Muto and ‘talent that comes around once every 100 years’ Hiroshi Tanahashi both strike a pose at the san–shichi position on the long hanamichi when they enter.

The hanamichi, the device that creates oneness of the stage and the audience.

It’s not just that it doesn’t grow old. Kabuki is filled with similar techniques to build hype in the theater space that has even become adopted in other genres.

Text: Kowloon Joe

Born in Tokyo, 1976. Writer and editor. Writes mostly about pop culture and traditional performing art. Has edited countless publications. Pens the series “Wakaki geinoshatachi” in the magazine Bungakukai (published by Bungeishinju). Published works include Memorīsutikku: Poppukaruchā to shakai wo tsunagu yarikata (Memory stick: How to connect pop culture and society) from DU Books.

Illustration: Kan Takahama

Born in Amakusa, Kumamoto Prefecture. Graduated from the University of Tsukuba School of Art and Design. Published works include Mariko Parade co-authored with Frédéric Boilet (Ohta Publishing Company), Yellowbacks (Yugaku Shorin), Awabi (Yugaku Shorin), Nagi-Watari and Other Stories (Kawade Shobo Shinsha), 2 Espressos (Ohta Publishing Company), Yotsuya-ku Hanazonocho (Takeshobo), Sad Girl (Leed Publishing), and Cho-no-Michiyuki (Leed Publishing). Received a best of short stories award for Yellowbacks from The Comics Journal in 2004. Received an Excellence Award in the Manga Division for Nyx’s Lantern at the 21st Japan Media Arts Festival in 2018. Highly regarded overseas.